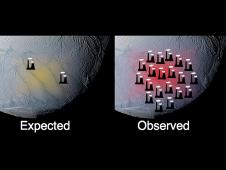

This graphic, using data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft, shows how the south polar terrain of Saturn's moon Enceladus emits much more power than scientists had originally predicted. Image credit: NASA/JPL/SWRI/SSI

NASA’s Cassini mission has been studying Saturn and its moons since it arrived at Saturn in 2004, seven years after its launch. Recent data from the probe, published in the March 4th edition of the Journal of Geophysical Research, showed a much greater level of internal heat on the moon Enceladus than expected.

The Cassini spacecraft focused its infrared spectrometer on the south pole of Enceladus, one of the many moons in orbit around Saturn, and registered internal heat-generated power in the region of 15.8 gigawatts. Scientists had only expected output to be in the range of megawatts at the most. Instead what they found was equivalent to the output of about 20 coal-fuel power plants here on earth. Geologically speaking this is over two and a half times the thermal energy of all the hot springs in Yellowstone combined.

“The mechanism capable of producing the much higher observed internal power remains a mystery and challenges the currently proposed models of long-term heat production,” said Carly Howet lead author of the study, and member of the infrared spectrometer science team.

Like many of the moons so far out from Sun, Enceladus has an icy outer layer, but the recent discovery, along with previous evidence of salty sub surface water, increases the chances that a liquid ocean may exist below the ice.

![Herbal Reference Substances are Key to Everyday Products <!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons above -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style " addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/herbal-reference-substances-are-key-to-everyday-products/3512112/' >

<a class="addthis_button_facebook_like" fb:like:layout="button_count"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_tweet"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_pinterest_pinit"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_pill_style"></a>

</div>When it comes to quality control testing and the development of new products, Botanical Reference Materials (BRMs), also known as Herbal References are critically important. To help companies ultimately obtain all-important FDA approval, the Food and Drug Administration provides in its guidance a recommendation that […]<!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons below -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style addthis_32x32_style" addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/herbal-reference-substances-are-key-to-everyday-products/3512112/' >

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_1"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_2"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_3"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_4"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_compact"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_bubble_style"></a>

</div>](http://newstaar.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Achillea_millefolium_flowers-100x100.jpg)

![Quality Electrochemical Biosensors are Critical for Medical, Food and Chemical Industry <!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons above -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style " addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/quality-electrochemical-biosensors-are-critical-for-medical-food-and-chemical-industry/3512086/' >

<a class="addthis_button_facebook_like" fb:like:layout="button_count"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_tweet"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_pinterest_pinit"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_pill_style"></a>

</div>A number of industries have, at their core, a need to frequent or even continuous analysis of biological media. These include the medical and pharmaceutical fields, biotech firms, and food and chemical companies. To maintain quality standards and develop new products, these industries rely heavily […]<!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons below -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style addthis_32x32_style" addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/quality-electrochemical-biosensors-are-critical-for-medical-food-and-chemical-industry/3512086/' >

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_1"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_2"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_3"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_4"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_compact"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_bubble_style"></a>

</div>](http://newstaar.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Electrochemical-Biosensor-100x100.jpg)

![Company Develops Industrial Mixers Well-Suited for both Fragile and Explosive Products <!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons above -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style " addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/company-develops-industrial-mixers-well-suited-for-both-fragile-and-explosive-products/3512071/' >

<a class="addthis_button_facebook_like" fb:like:layout="button_count"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_tweet"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_pinterest_pinit"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_pill_style"></a>

</div>Industrial drum mixers are normally applied to blend mixes of varying viscosities such as adhesive slurries or cement. Some of these mixers have the capability of blending mixes of very different particle sizes such as fruit and ice cream, and gravel and cement slurry. The […]<!-- AddThis Sharing Buttons below -->

<div class="addthis_toolbox addthis_default_style addthis_32x32_style" addthis:url='http://newstaar.com/company-develops-industrial-mixers-well-suited-for-both-fragile-and-explosive-products/3512071/' >

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_1"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_2"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_3"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_preferred_4"></a>

<a class="addthis_button_compact"></a>

<a class="addthis_counter addthis_bubble_style"></a>

</div>](http://newstaar.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/bandeau-sofragir2-100x100.jpg)